Madama Butterfly unveiled: meet Costume Designer Mariko Ohigashi

Costume Designer Mariko Ohigashi has a personal connection to Calgary Opera’s production of Madama Butterfly, onstage Nov. 1-7, which director Mo Zhou centres in 1940s Nagasaki, shortly after WWII. Her grandmother was a teenager in Hiroshima when she survived the atomic bomb. Her accounts of that time, along with historical photographs from post-war Japan, are a bed of inspiration for Ohigashi’s design concepts. We spoke with Ohigashi about how her detailed costuming builds the complicated world of Butterfly:

What do you find compelling about the story of Madama Butterfly?

“It's hard to say, because most of the time Madama Butterfly makes me feel deeply sad. But what I find compelling is how the story can be interpreted and experienced in different ways. I sometimes wonder how I might view this story if I had a different cultural background or gender identity. Similarly, someone might respond to it one way as a teenager and feel something entirely different later in life. Whether intentional or not, that space for interpretation invites me to keep reflecting on who Cio-Cio-San is.”

What historical context inspired your costume design for this production?

“The setting of this production — Nagasaki, one year after the atomic bombing — had the strongest influence on my approach. This context felt especially personal, as my grandmother is a hibakusha, a survivor of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. She was just 14 years old when she experienced it.

“For this production, I spoke with her about her memories and experiences. At the same time, I researched hundreds of photographs taken in postwar Japan. I studied them carefully, trying to absorb the atmosphere of that time through my own eyes. Just as my grandmother described — ;there was nothing’ — the images, especially those taken right after the war ended, revealed a landscape of confusion: burned-out cities, extreme shortages of food and clothing, and visible scars of war everywhere.

“And yet, amidst all of that, people were doing the best they could to survive. Those images of people pushing forward through such chaos stayed with me throughout the design process.”

How does your costume design support the storytelling? What can we understand about various characters from what they wear?

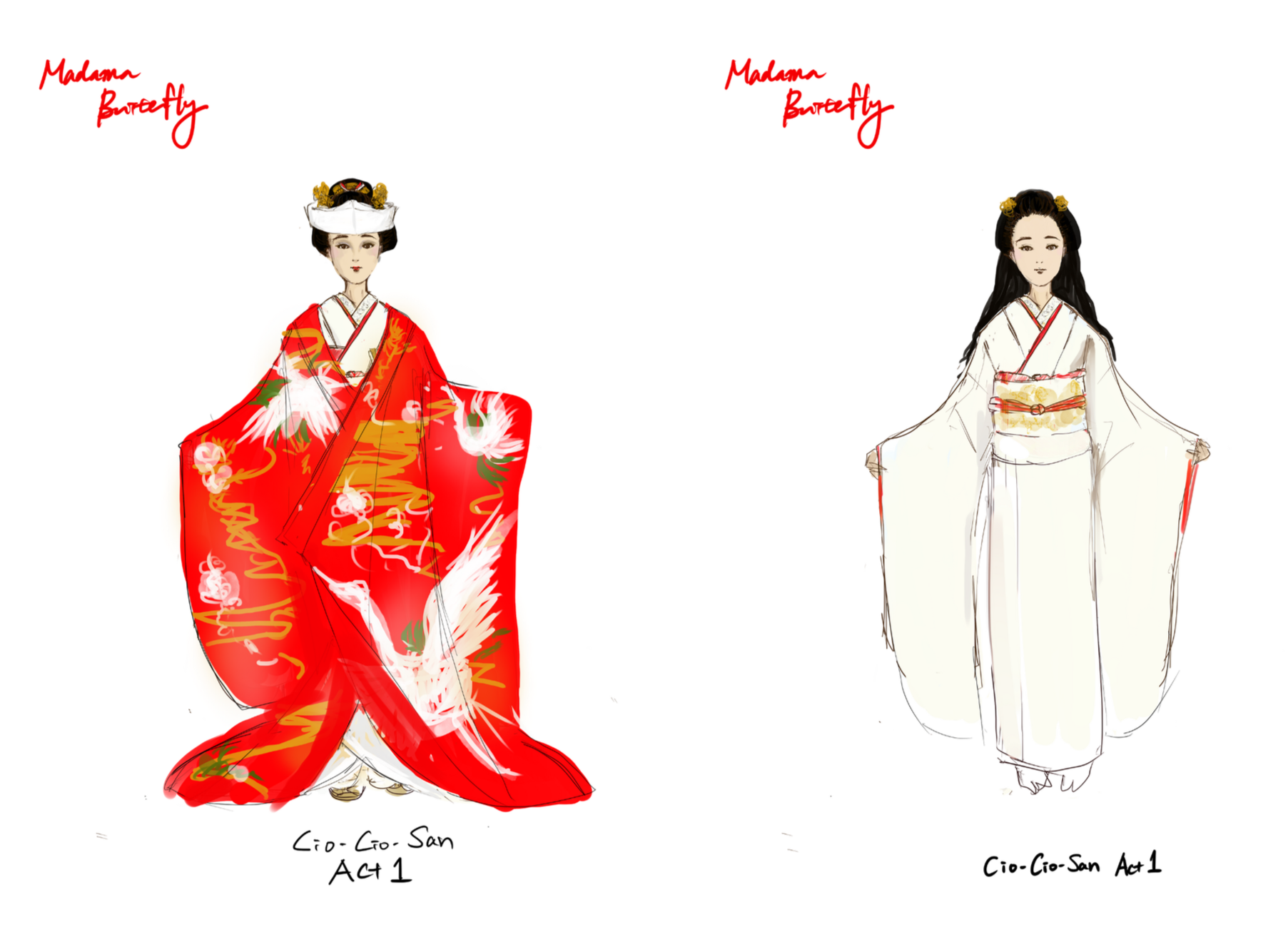

“In Act I, I wanted to portray a time when there was truly nothing — and yet, people faced forward, living with creativity and strength. For the wedding scene, I imagined people doing their very best with what little they had. Mo and I talked about Cio-Cio-San wearing a beautiful kimono that survived the bombing — perhaps with slightly scorched edges. The female Japanese guests would wear the only kimono they had left, or borrow one, trying to use this opportunity to present the best version of themselves. Indeed, I saw many photographs of people in brightly coloured kimonos after the war. People were finally able to wear these colourful, luxurious garments that had been tucked away during the war.

“Goro, too, is doing his best — dressed in his own version of Western clothes, probably cobbled together from the black market. In Act I, he’s far from elegant, but he is trying to survive — again, in his own way — and make his way up. While Madama Butterfly is often portrayed glamorously and romantically, I wanted to weave subtle traces of the postwar context alongside the vibrant colours of the kimonos. I hope you can, in some way, feel the ‘real’ people who survived that time.”

For this Butterfly, what costumes are you most proud of, or most excited to unveil to Calgary audiences?

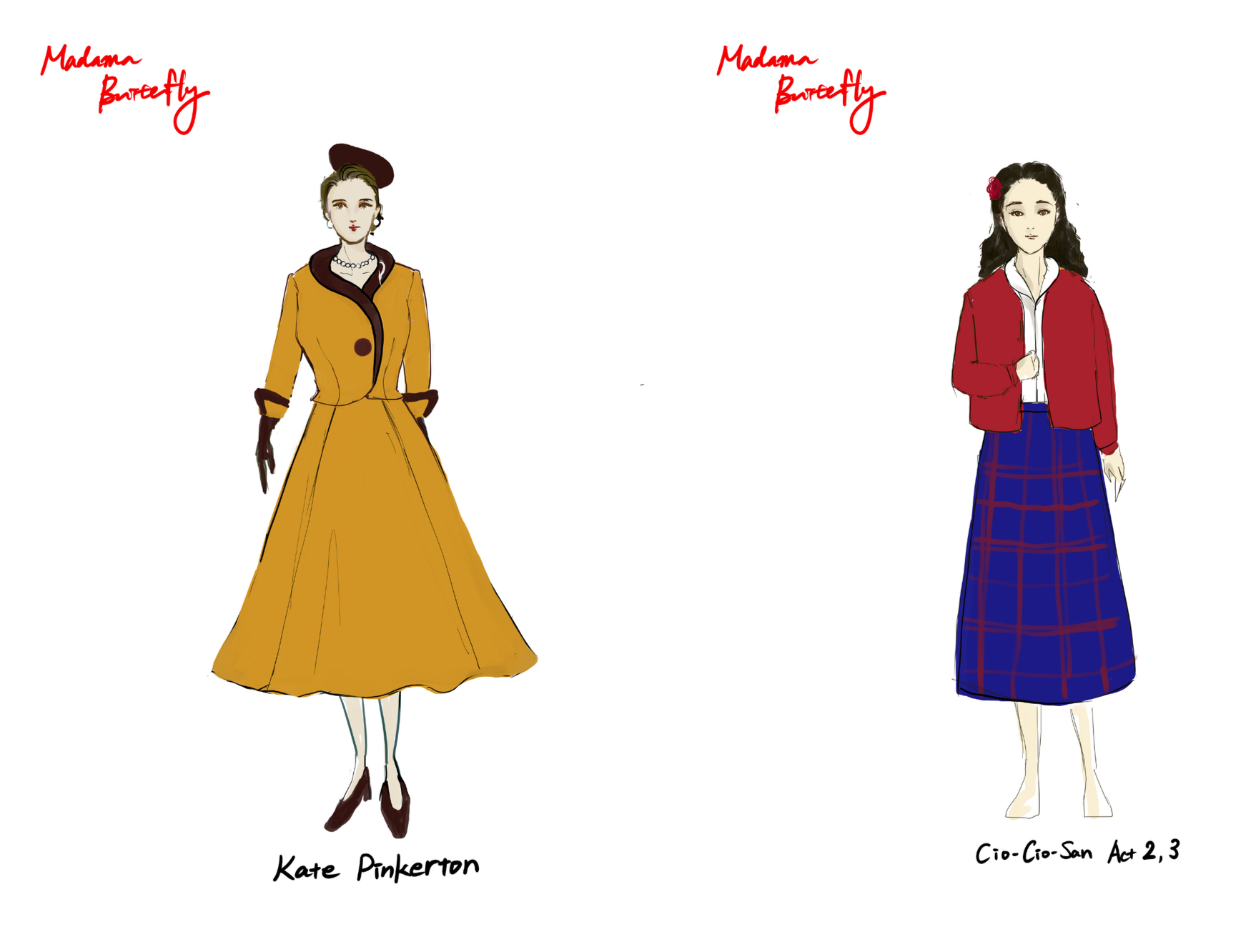

“I think the contrast between Butterfly and Kate (Pinkerton’s new wife) in Act III will be especially striking. By Acts II and III, Cio-Cio-San has become very poor and has probably sold most of her clothes. Yet, she does her best to dress in Western style, even if that means transforming the only kimono she has left — her favourite one — into a Western skirt. However, Kate’s visit makes Cio-Cio-San face the difficult truth that, no matter how much she tries, she may never fully be seen as American.”

How should we approach pieces of art which don’t appear to “age well”? How do we know whether to shelve a piece or try and preserve it?

“For me, what’s important in art is being able to relate to the emotions expressed. When I can connect with the characters — regardless of who they are, where they come from, or whether I agree with them — that’s what makes the experience of art meaningful. I believe both creators and audiences have a role in helping find connections that are universal and still feel relevant today.”

What do you hope audiences will take away from this production?

“Rather than seeing Madama Butterfly as a distant, romanticized tragedy, I hope we can approach it more realistically — asking what it truly means for a 15-year-old girl to navigate life under the shadow of war. Together with the audience, I hope we can explore this while immersing ourselves in Japanese culture.”